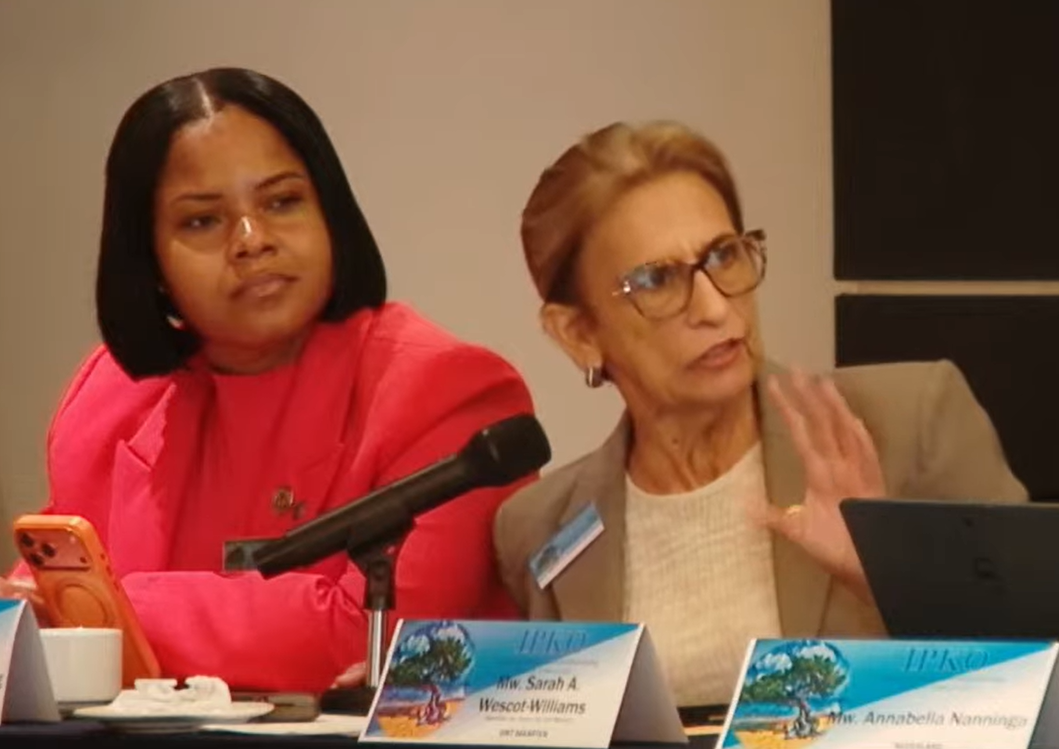

Wescot-Williams tells IPKO current supervision no longer fits today’s reality

ORANJESTAD, Aruba--President of the Parliament of St. Maarten and delegation leader MP Sarah Wescot-Williams used the financial supervision discussions at IPKO to argue that the post 10/10/10 framework has not delivered the “clean slate” narrative often implied in debates about debt restructuring, and that the Kingdom must now redesign supervision to reflect today’s realities for small island states.

“The debt restructuring that happened with 10/10/10 put St. Maarten in a negative position, not in a ‘clean slate’ or ‘fresh start.’ That’s just a statement, that’s a fact,” Wescot-Williams said.

She added that, under present conditions, reaching a balanced budget is not realistic unless the country “mentally cheat[s] ourselves,” which she described as excluding items that must be accounted for.

“There is no way unless we mentally cheat ourselves to get to a balanced budget on the current circumstances,” she said. “What do I mean with cheat ourselves? Not to take into consideration and into our budget things that need to be taken into consideration.”

Wescot-Williams said the situation cannot be addressed properly if St. Maarten’s small island development state character is not treated as a core factor in financial governance.

“If we are not going to consider the small island development state character of these islands, where climate justice and debt justice are real issues, we will never get out of the so-called CFT, the way we know it now, supervision, yes,” she said.

She stressed that circumstances in 2010 and today are not comparable, and warned that continuing in the same supervisory structure without modernization would amount to self-deception.

“We cannot compare the circumstances of 10/10/10 with the circumstances of today,” Wescot-Williams said. “We now need to talk about how do we change that kind of a supervision in order to make it applicable to today otherwise we’re all fooling ourselves.”

Wescot-Williams also indicated that she has the sense that officials within the CFT recognize the mismatch between then and now.

Werleman presentation frames supervision debate around “balance”

Her remarks came in the context of a detailed presentation delivered for the Aruba delegation by Derrick Werleman, which examined the balance between financial steering, supervision, and autonomy across the Caribbean countries within the Kingdom. He is a senior Aruban public official who serves as Director of Directie Financiën, the government’s finance directorate

Opening the session, Aruba representatives stated that Aruba’s current financial position is strong, citing a projected 2026 surplus of 2.6 percent of GDP and referencing recent CFT correspondence on Aruba’s progress. Werleman then walked delegations through how the supervision landscape is structured, why it developed differently across countries, and how powers and enforcement work in practice.

Different histories, one convergence: financial supervision

Werleman explained that the financial oversight frameworks across the Kingdom emerged through different historical routes. For the former Netherlands Antilles, he referenced the institutional split of 10/10/10 and the debt restructuring that accompanied it. For Aruba, he described a separate path rooted in debt sustainability concerns that brought financial supervision into focus more than a decade ago.

Despite different starting points, he emphasized that the systems converge on similar objectives: rules that aim to keep public finances sustainable, define fiscal space, and set out what happens when countries deviate from agreed norms.

Three core domains across frameworks

Werleman outlined that the existing and proposed rules generally revolve around three domains:

• Budgeting, including fiscal targets and annual budget requirements

• Financial management, including execution and accountability standards

• Financing, including borrowing, debt management, and how governments access funds

He noted that while the details and wording differ, the structure of supervision across frameworks concentrates on these three pillars.

Norms, enforcement, and who ultimately decides

Werleman compared the main supervision models discussed at IPKO, including the RFT (applying to Curaçao and St. Maarten), the LAft, and the proposed package for Aruba which he described as aiming to simplify standards, with more emphasis on a debt ratio and a primary financing surplus.

He also described how supervisory bodies function and where final authority lies. In his presentation, he distinguished between the monitoring and advisory roles of bodies such as the CFT and the CAft, and the decision-making authority that can ultimately rest with the Kingdom Council of Ministers in specific situations, including when financial norms are not met or when critical budget documents are not produced.

Autonomy, “room to govern,” and public accountability pressures

A central theme of Werleman’s presentation was how compliance with norms affects a country’s practical space to govern. He explained that meeting fiscal standards generally preserves autonomy in policy choices, while deviations can trigger escalating oversight and formal intervention.

He also addressed points that have historically caused friction, including how and when supervisory findings are published, and the tension that can arise when public-facing advice intersects with domestic political responsibility.

COVID liquidity support and the country package context

Werleman further placed today’s supervision debate in the post COVID context, referencing liquidity support loans introduced during the crisis and the later shift toward conditions aimed at driving reforms. He described the evolution from emergency response into a more conditional framework tied to structural reform expectations, including the country package track.

Linking supervision reform to today’s island realities

Wescot-Williams’ comments positioned St. Maarten’s concern as not simply technical, but structural: that supervision designed around a 2010-era baseline cannot be treated as fit for purpose in 2026 without incorporating current realities, including climate vulnerability and the fiscal constraints of small island states.

Her call at IPKO was for a serious redesign of supervision so that it remains credible and effective, while also being applicable to present-day conditions, rather than demanding outcomes that can only be reached by excluding real costs from national budgeting.

Join Our Community Today

Subscribe to our mailing list to be the first to receive

breaking news, updates, and more.