Historian Brooke N. Newman: The Crown Enslaved, Sold, and Profited

.jpg)

The Smithsonian Magazine on January 26, 2026, reframed the British monarchy’s relationship to slavery as direct governance, not distant symbolism. Rather than focusing only on royal charters, court culture, or passive “benefit” from empire, historian Brooke N. Newman argues the Crown functioned at times like an owner and administrator, acquiring enslaved people through government operations, military policy, conquest, and inheritance law, then treating human lives as assets that could be worked, transferred, or sold.

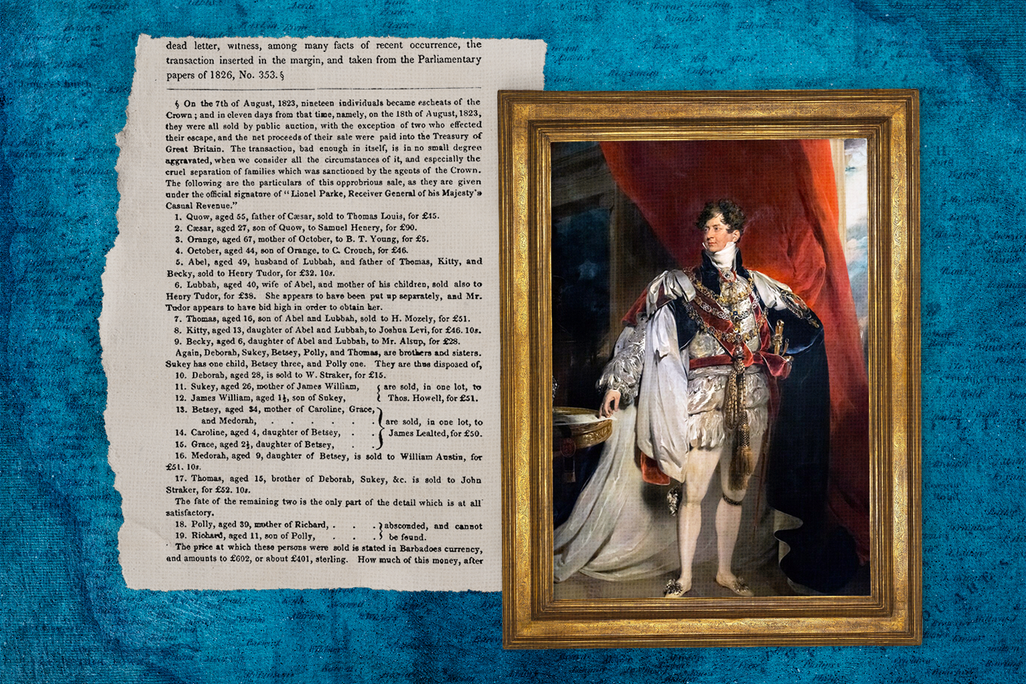

Her central case study is an 1823 episode in Barbados: enslaved people became Crown property after an enslaver died without legal heirs, then most were auctioned in Bridgetown in the name of George IV. Newman reconstructs the sale at the level of individuals and families, naming parents, children, and siblings, and describing how routine procedure produced family separation, with the proceeds landing in royal accounts. The point is not that this was unusual, but that it was lawful and bureaucratic, a window into how imperial systems made royal slaveholding ordinary.

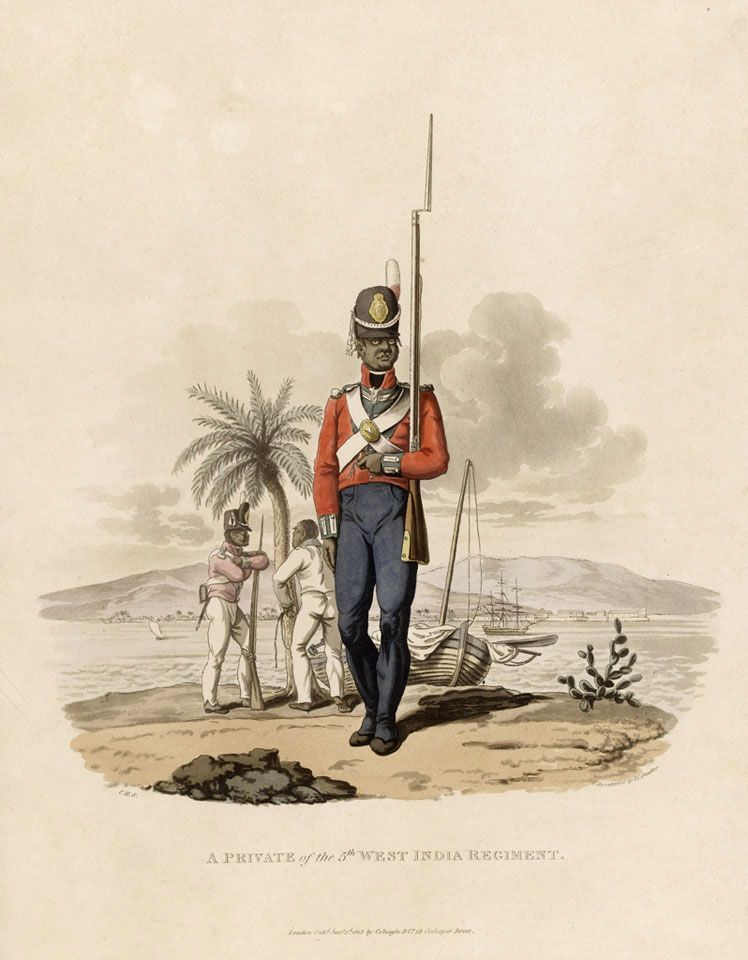

From there, the article widens into a longer institutional story. Newman traces Crown slaveholding back to the 18th-century naval dockyards, where officials sought an enslaved labor force to build and maintain bases and ships. She then follows the pattern into wartime military expansion, when the British state purchased large numbers of enslaved men for service in Caribbean regiments, and later into the post-1807 era, when Britain outlawed the trans-Atlantic slave trade but still relied on coerced labor through forced conscription and the absorption of enslaved people captured through colonial seizures or legal forfeitures. Even reform debates, in Newman’s telling, centered on property management and precedent, not the basic question of freedom.

The result is an article that pushes readers to see the monarchy’s role as operational: slavery was not simply tolerated under the Crown, it was also administered through offices, accounting, and policy, including moments where royal authority could have been used to emancipate people already under the king’s legal ownership but was not.

Key dates and milestones

- 1689: An archival document cited by Newman links shares in the Royal African Company to the king via Edward Colston.

- 1729: Rear Admiral Charles Stewart reports severe labor shortages while building a naval base on Navy Island, Jamaica, and proposes Crown purchase of enslaved labor.

- September 1730: Naval officials endorse the plan to buy enslaved workers “for His Majesty’s service,” including boys.

- Mid-18th century: The king becomes a legal owner of enslaved people in Jamaica, known locally as the “King’s Negroes.”

- 1750: Naval officials order the sale of enslaved women and girls owned by the Crown on Navy Island, calling them “of no use.”

- 1795 to 1808: The Crown buys more than 13,000 enslaved men for military service in the West India Regiments, using public funds.

- 1807: Britain outlaws its participation in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, while coerced systems persist through forced conscription and colonial control.

- 1819: Dominica’s governor asks the Colonial Office for guidance on enslaved people acquired by the Crown, raising the question of manumission.

- August 7, 1823: Enslaved people in Barbados become Crown property after their enslavers die without legal heirs.

- Mid-August 1823: A public auction in Bridgetown sells most of those people in the king’s name, separating families.

- 1823: A second appeal by Dominica’s governor again urges freeing people acquired by escheat rather than selling them.

- 1831: Newman reports the Crown frees enslaved people in its possession.

- 1834: Slavery is abolished in British colonies and replaced by apprenticeship.

- 1838: The apprenticeship system ends.

- January 26, 2026: Newman’s Smithsonian Magazine article is published alongside discussion of her 2026 book, The Crown’s Silence: The Hidden History of the British Monarchy and Slavery in the Americas.

Newman’s reporting leaves little room for comfortable distance: the monarchy was not merely adjacent to the machinery of slavery, it was woven into its administration. The power of the article is its insistence on names, families, and the paper trail of bureaucracy that converted human lives into entries on a ledger, then into cash for the royal treasury. By placing Barbados, Jamaica, and the wider Caribbean at the center of that record, the piece reframes old debates about complicity into a sharper question of accountability: when a system could operate smoothly, legally, and in the king’s name, the suffering was not an accident of empire, it was part of its design.

"This question echoed far beyond Barbados. Why had the monarchy refused to use its own authority to end slavery where it could? The answer lay in the priorities that had shaped royal slaveholding in the Caribbean from the outset. Enslaved people were valuable labor. They were assets. They were revenue.

From the dockyards of 18th-century Jamaica to the barracks of the West India Regiments to the auction block in 19th-century Barbados, the crown treated enslaved Africans and their descendants as tools of empire. Royal ownership did not shield families from violence; it organized that violence through law, bureaucracy and accounting.

The lives of Quow, Orange, Abel, Lubbah, Betsey, Deborah, Sukey, Polly and their children were not anomalies. They were the human consequence of a system the British monarchy had long profited from, sustained and defended.

The crown did not free the enslaved individuals in its possession until 1831.

When Britain finally abolished slavery in 1834, compensation equivalent to roughly 17 billion pounds (around $23 billion) today flowed to enslavers. No such restitution was offered to the people whose lives and families had been torn apart, whose labor had fortified dockyards, bolstered regiments and filled royal coffers.

Their names survive only in fragments: in sale lists, plantation account books and the margins of imperial records. Yet their experiences force a reckoning with an uncomfortable truth. Britain’s monarchy was not merely a passive participant in trans-Atlantic slavery. It was deeply, deliberately entangled in it—and enslaved people paid the price."

The piece can be read here: www.smithsonianmag.com

Dr. Brooke Newman is an associate professor at Virginia Commonwealth University and a fellow of the Royal Historical Society. She specializes in the history of early modern Britain and the British Atlantic, with a focus on slavery and its legacies. She is the author of the award-winning book A Dark Inheritance: Blood, Race and Sex in Colonial Jamaica (Yale, 2018), and The Crown's Silence: The Hidden History of the British Monarchy and Slavery in the Americas (Mariner, 2026). Her writing and research have been featured in the Guardian, the Washington Post, Der Spiegel and i-news, and she has served as a historical expert for HBO's “Last Week Tonight,” Vox, the BBC and NPR, among others.

.jpg)